written by Vanessa Pike-Russell

‘How old’ is an oft asked question and hard to answer. Lifespan is similar. They both depend on many factors such as diet, exercise, moulting frequency, pecking order, species and availability of seashells. In this article, I will touch on a few of the factors, and finish with some hints on how to get a rough estimate of the size and age of your hermit crab. A big ‘thank you’ to Carol of CrabWorks for her permission to use her wonderful photographs, and for being such an inspiration to us all!

How fast a hermit crab grows usually depends on what it eats, drinks and how much it eats and drinks! The growth cycle of a land hermit crab is based on a process known as moulting, which is often triggered by the amount a hermit crab a hermit crab eats and drinks. The body grows within the hard outer skeleton. Just as when we are young and our feet are growing, but the shoes do not. We change our shoes when the tough outer shell (or shoe in this case) no longer fits and constricts about your larger foot. So to do shoes feel uncomfortable when there is fluid retention, such as when travelling or after eating salty foods. Sometimes the shoe ‘splits’ apart as growing feet stretch the material, causing weak areas (often around glue lines) to come apart.

“Typically premoult animals enter their burrows with their abdomens markedly swollen by food reserves… After moulting the animal eats its exuviae,which contribute organic materials and calcium salts needed for the new skeleton… Very little information is available in regard to moulting of Coenobita. Coenobita clypeatus is reported to hide during the process most of which occurs in the shell (de Wilde, 1973). There is a noticeable reduction in activity for several days prior to the moult and after ecdysis the exuviae are positioned just in front of the mouth of the shell (A.W. Harvey, pers. comm.). During calcification the new soft skeleton of the chelae and other walking legs is moulded to fit the shape of the shell. If the animal increases markedly in size it may no longer fit neatly within the old shell and a rapid trade up in shell size may be necessary to avoid water loss and predators. There is no information available on calcium balance or storage through the moult or on growth increments of Coenobita. Coenobita clypeatus grows up to 500 g if large-enough shells are available” (Greenaway, P. 2003 p. 21) Land Hermit Crabs that are eating foods high in calcium, fiber, chitin and foods high in nutrients their bodies need will often have a much higher moulting rate; which slows with age or lack of larger seashells. If a crab is in a seashell, which is snug with no alternatives, they will not moult as readily as one with a vast selection.

Exercise is known to increase hunger, and thus will affect the rate of moulting. In the wild, land hermit crabs have been known to walk many miles a night, and graze on foods along the way. It would depend on location as to the amount of exercise and grazing a hermit crab will do. We can full fill the need to walk by providing a plastic hamster wheel in the crabitat. It is important to provide a multitude of climbing surfaces as well.

“In the summer months, food availability has a major affect on shedding activity. If a crab does not satisfy the physiological need to shed (increased muscle tissue, body cavity ‘cramping’, etc.), it will not enter the molting cycle. In other words, if it doesn’t get adequate nutrition it’s not going to grow.” (Oesterling, M. 2003)

Scientist Mike Oesterling of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science has noted this in Blue Crabs.

Hermit Crabs are social animals, and as such, there is usually a ‘pecking order’ among groups or colonies. As with many animals and organisms, when there is a scarcity of resources you will see a ‘pecking order’ among hermit crabs. The resources most important to hermit crabs being protein and calcium-rich foods and varied diet; hiding spots; space to dig down to moult; different sizes of seashells; water; and ocean water).

If a crab is ‘top crab’ than it would get the most food, like with puppies and seagulls. We see this on a small scale within the crabarium, where hermit crabs vie for position in the food bowl or a favourite hiding spot. I have often watched my jumbo hermit crabs fighting for access to the salt-water bowl or treat dish. It is not unusual for them to fill the bowl completely and keep other hermit crabs away, defending their right to eat first.

Hermit Crabs grow through moulting. If you notice a hermit crab pre and post moult you will see very little difference, but over ten or twenty years it is quite significant. Another way to tell age is to look at the thickness of antennae and the little ‘teeth’ on the cheliped/grasping claw.

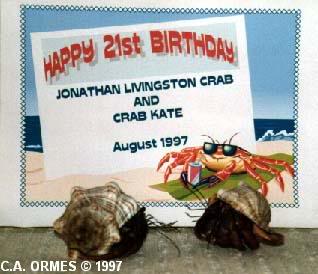

Carol of CrabWorks has had the same two hermit crabs for twenty-six years. On her photo page, she shows how much they have grown over 25+ years in captivity. Carol believes Jonathon and Kate would have grown more than they have in captivity. Not only are her crabs limited by the size of seashells, their nightly roaming around her sunken living room do not compare with that of their wild counterparts. (Carol lives in Florida which is the native habitat of C. clypeatus so she is able to allow her hermit crabs to roam outside of the crabitat.)

In the wild hermies are known to walk miles a day so they would eat more to sustain them. They might not get the yummy foods they eat in captivity, but would snack on the woods and shells etc as well as ‘normal’ foods like carrion (fruit, fish, meat etc that they find on the beach, among mangroves or on the forest

Carol feeds her hermit crabs a range of foods, which she believes are similar to what they would come across in the wild. Their favourite is Brown Oak Leaves,

“I usually pick up the fresh brown leaves from a sidewalk, not from the ground. I do inspect them for bugs, mold, and weird spots.

There are so many available that choosing is easy”.

The leaves could be partly responsible for the wonderful dark chocolate colour of Jonathon and Kate, but that is only the start of the fantastic treats her hermit crabs consume on a regular basis.

For calcium, Carol gives them “boiled eggshells about once a week. They like spinach leaves, a little lettuce, brown oak leaves and boiled or microwaved tree bark (not cedar or pine). They just love bark and oak leaves. These too: bananas, apple slices, scrambled eggs on Saturday, a variety of dry cereals (including Kashi), occasional cookies. I just keep changing and trying new foods. They don’t like the same foods too frequently–or even two nights in a row! I do sprinkle sea salt on their food a couple of times per week and am right now trying a little sea salt in a second water dish. I’ve already seen them drinking it.”

When a crab moults, they often regenerate any limbs or body parts that were lost between moults. Often the regenerated limb is often much smaller after the first few moults, until it slowly reaches the size of the lost limb. This is one of the reasons why the size of a hermit crab’s cheliped is not always a true indication of a hermit crab’s age.

So what is the scientific way to tell how old a hermit crab is?

“In general, large crabs are older than small crabs. The only way you can accurately estimate your crab’s age is if it dies. Then the otoliths, small concretions of mineral deposits, which sit atop the crab’s balance organ (located at the base of each antennule), need to be removed. The otoliths can be sectioned and the number of growth rings counted”

Fox, S. 2000

In my experience, older crabs have more ‘teeth’ or knobs on the claw. The photo above is of my hermit crab BigRed. In the photo (right) you can see a photo of BigRed and BFG playing next to a tennis ball to indicate their sizes. Another difference is thicker antennae, if they have not been damaged in a moult. Many of my jumbos have very long antennae, which are thick and look much different to the fluttering antennae of younger crabs.

In addition, many of my jumbos have ‘setae pores’ which are like big bumps on the exo skeleton. To touch them it feels so different to the supple, soft exo of smaller hermies. It is almost like a lobster’s shell, in a few places, if that makes sense. Big Friendly Giant, my largest hermit crab, had a very rough exoskeleton, which felt like a mixture of leather and lobster shell. Strange, but true!

There are also many differences in size between hermit crabs of different species. The largest of all species of land hermit crabs is the Coconut Crab, recently classified as a branch of Coenobitidae (land hermit crab). A stock assessment of coconut crabs was undertaken in Vanuatu during 1994. A report was written by Fletcher, W.J. and Amos, M. in which they found that Coconut crabs “are the largest land-dwelling crustaceans, having been found to attain weights in excess of 5kg. Coconut Crabs are sexually mature at approximately five years of age, at a size of 22-25mm tail length.”

Species common to the United States of America really do vary in size, shape and colour. Jonathon and Kate of CrabWorks are both known colloquially as Purple Pincers, due to the dark purple colour on their ‘pincers’ or claw. They are often distinguished by their dark colouring, but the eyes of a Purple Pincer are much different to other species, being rather rounded and not compressed as in the ‘Ecuadorian’, ‘Indian’ varieties found in pet stores across the country. Sometimes Purple Pincers, which are usually found in Carribean areas, have a rather rich red colouring, as observed in the photo of ‘Freebie’ by Carolyn below.

Freebie has a colouring similar to that in the Strawberry Land Hermit Crab (Coenobita perlatus). However, Freebie has rounded eyes, whereas C. perlatus usually has a compressed eye, as with the photo of the Australian perlatus variety at right. As you can see, there is quite a difference between the two hermit crabs. Freebie is an example of a C. clypeatus that is labelled as ‘red’, often confused with C. perlatus.

Pacific hermit crabs(C. compressus), also known as Ecuadorians) found in many areas Ecuadorians are usually smaller than PP’s. It is rare to find a large Ecuadorian hermit crab, although we do not really know why. Perhaps it could be in part due to their need for deeper substrate to dig in for moulting, their intolerance of the cold or lack of suitable large shells. Other factors could be related to location and predators, with larger hermit crabs becoming a tasty morsel for animals higher up on the food chain. The photo of Ichabod (right) is very similar to that of rusty, an Australian land hermit crab.

Ecuadorian Land Hermit Crab (C. compressus) Australian Land Hermit Crab (C. variabilis)

Their close cousins in Australia (C. variabilis) have similar compressed eyestalks, and the vulnerability to temperature fluctuations, and a preference for a diet high in fruit and nuts. The Australian species can grow up to baseball size in areas of Australia. These ‘Jumbo’ crabs love to wear a very lightweight shell which is easy for them to carry around. I think the size difference is in part due to their ability to find larger shells and the fact that many areas where land hermit crabs are found are often remote locations with little if no human population or development.

Size and Aggression, Competition for Shells

In the last two years, I have observed over thirty jumbo Australian land hermit crabs, and they really opened my eyes to aggression and social order among colonies of larger hermit crabs. Most of the crabs came straight from the wild, and were in seashells that were ill fitting or broken. Seashell fights were rife and more than a few hermit crabs killed for their shell.

It makes you realise just how important a resource it is, and the reality of ‘survival of the fittest’. The faster the hermit crabs changed into a new or different modified seashell protection, the sooner they settled down and established their status within the group.

Many of the Hermit Crabs that had a seashell without any obvious defects remained in the shells for a year or more, even when presented with over a hundred (100) seashells from which to choose. They seemed to favour Tunna shells, Turban shells, Fox shells, whelk shell, and various specimens from the Murex family. Smaller hermit crabs love the Nerite shells, which are found in large proportions along the coast of Australia. Other popular shells are: Thais (rock shells) and Turban shells.

This experience with older, larger hermit crabs helped me to understand why larger hermit crabs were rare in many parts of the world. As it gets harder to find a large shell, hermit crabs must become more aggressive and fight for their survival. If they cannot find a light seashell with sufficient space and watertight properties, they will soon outgrow their current seashell; dehydrate from lack of a fitting seashell; or be attacked. Either way, their chance of survival is limited. This could be why many larger hermit crabs in captivity do not seem to grow much once they reach a certain age. If they could receive a suitable diet, exercise regularly and have a range of suitable seashell sizes and types, they will be more inclined to grow. If they have to remain in the same seashells for years on end, they may experience a stunted growth, restricted by the size or dimensions of their seashell.

When sizing hermit crabs, I usually sort by cheliped (grasping claw) size, with larger claws related to age, but as we discussed earlier, this method isn’t very scientific since hermit crabs often loose claws in stressful situations, and they may take some time to return to original size.

BBC One video on hermit crab housing and the chain reaction a single shell change can trigger:

So, what is a general rule of thumb to follow?

If you look at the photo galleries of Jonathon and Kate, it shows some baby hermit crabs back in 1977, some rather large to jumbo hermit crabs in 2003. Therefore, we know that Jumbo crabs are at least twenty to thirty (20-30) years of age. Hermit Crabs under a golf ball size would most probably be under ten (10) years of age, and medium size (mandarin size) at least in their twenties (20+). The photo to the left shows the change in size over 25+ years of growth in captivity.

Teeth size, antennae width and texture of the exoskeleton are all indications of age although not very scientific basis for identifying the age of a land hermit crab. Once more, it all depends on the availability of resources, location and species as to determining age.

I guess the important thing is to respect the life of the crabs in our care, and appreciate the sizes they can grow to in the wild. In the grand scheme of things, is it really that important to know their age? Of course not, but it is awe-inspiring to see a jumbo crab, and know that he or she is most probably older than you are!

Photo Credits:

Mandy D

Carol Ormes CrabWorks Photos and Sounds Gallery URL: http://geocities.com/hermit_crabs/carol- dead link URL: http://crabworks.angelfire.com/

Our Spotlight on Carol Ormes

Maryanne Ponte’s Photo Gallery URL: http://photos.yahoo.com/peripolak- dead link

University of Massachusetts Amhurst: Biology 497H – Tropical Field Biology.

St. John, USVI March 16, 2001 to March 25, 2001 Photo Gallery

URL: http://www.bio.umass.edu/biology/troptrip3/

Vanessa Pike-Russell

Vanessa’s Site

Vanessa on Flickr

References:

- Fletcher,W.J. and Amos, M. 1994 Stock Assessment of Coconut Crabs. ACIAR Monograph No.29 32p

- Mike Oesterling of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. Quote relates to blue crabs.

- URL: http://www.blue-crab.org/fullmoon.htm

- Fletcher, W.J., Brown, I.W., Fielder, D.R., and Obed, A. 1991b. Moulting and growth characteristics. Pp. 35-60 in: Brown,I.W., and Fielder,

D.R. (eds), The coconut crab: aspects of Birgus latro biology and ecology in Vanuatu. Canberra, Aciar Monographs 8. - Fox, S. (2000) Hermit Crabs : A Complete Owner’s Guide. pp. 27. Barrons Books : NY

- Greenaway, P. 2003. Terrestrial adaptations in the Anomura (Crustacea: Decapoda).

- In: Lemaitre, R., and Tudge, C.C. (eds), Biology of the Anomura. Proceedings of a symposium at the Fifth International Crustacean Congress,

Melbourne, Australia, 9-13 July 2001. Memoirs of Museum Victoria 60(1): 13-26. - Greenaway, P. 1985. Calcium balance and moulting in the Crustacea.

- Biological Reviews 60: 425-454. Herreid, C.F. 1969b. Integument permeability of crabs and adaptation

- Grubb, P. 1971. Ecology of terrestrial decapod crustaceans on Aldabra.

- Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 260: 411-416.

- Held, E.E. 1965. Moulting behaviour of Birgus latro. Nature (London) 200: 799-800.

- Osterling, M. Moulting and the Full Moon. Online article [URL http://www.blue-crab.org/fullmoon.htm]